|

| Vol. 41, No. 3, Fall 2011:Conversations |

|

Featured Article

The Hidden Curriculum of Standardized Exams for English Language Learners Standardized tests and assessment-based reforms have been even more widely implemented since 2001 when the U.S. Congress passed the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act. Provisions in the NCLB Act stipulates that English Language Learners (ELLs) are tested in Math and English beginning the year that they enter school or in the following year. Schools and districts must report the results of test data and show that ELLs are adequately meeting the standards set by the state and the federal government. However, as we are all aware, for newly arrived ELLs to meet the standards set by the state and the federal government measured by standardized exams in such short periods of time is not an easy task. Studies show that learning English, especially academic English, may take up to 7 years for a child (Cummins, 1991). Indeed, to handle cognitively demanding tasks in a language other than one’s own mother tongue takes time and effort both on the part of students and teachers. Another reason standardized exams are a challenge for ELLs can be found in the exams themselves. According to Reiss (2008), for some ELLs the process of reading a passage, answering the questions, and bubbling the answers on a separate sheet of paper may be a totally new experience. Testing styles are different in different parts of the world so it is no surprise that for some students standardized exams may be something that they have never had experience with. I still remember the startled face of a 5th grader I met in a New York City school from Uganda when I told her that all the questions in the test each have only one right answer. Teachers must be ready to talk to their students about standardized exams and the best ways to approach the questions. Below are some suggestions for working with ELLs on standardized exams, especially in the area of reading comprehension. Working with Students on How to Take Standardized Exams in Reading Comprehension Familiarizing students with multiple choice questions. Reiss (2008) states that

Teaching students that the answer is in the text. Students who do not have experience with reading comprehension standardized exams may not know that the answer is always in the text. Often times, in reading tests, children will read the passage, go to the questions and never look back at the passage again. Students must be reminded that the answer lies in the text and that the choices are merely answers in the text put in different words. An effective way to practice this idea is for the students to go back to the paragraph and underline the part that pertains to the answer with each question. This makes it clear that the answer always lies in the text and that they should go back to the text to find the answers. Working with students to choose the best answer. Many times in multiple choice reading questions, among the choices, there maybe two or more acceptable answers. Students need to be reminded that they are looking for the best answer to the question. Consider the example below:

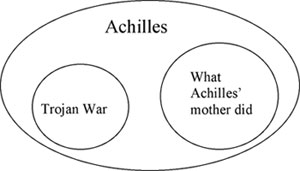

What is the above passage about? When confronted with such a question, many ELLs will say that the passage is about all of the choices, b through d, because there is mention of all the topics in the passage. Teachers need to keep in mind that questions such as “What is the above passage about” may be confusing to many ELLs. Some students may need explicit explanation and instruction in what each of the questions are asking for. The question in the example above is asking for the main idea of the passage and therefore the most comprehensive idea of the passage. An effective way to talk about this with students is to show that though topics, b, c, and d are all included in the passage, choices c and d are not the answer because they are apart of choice b. The passage is a story about “Achilles” who fought in the Trojan war and who was dipped in water by his mother. Teachers may convey this idea through a diagram that shows the relationship between the three ideas as the one below.  Helping students be aware of time constraints. Help students understand that the exam must be completed within a certain period of time and practice pacing. Teachers should know approximately how much time should be spent on a short reading passage versus a long paragraph, etc. and let the students know of such time expectations when practicing with short and long passages. When prepping students for tests, also help them be aware of time by letting them know when 5 minutes has passed, or when 10 minutes has passed so they know what that time feels like. Such practices may help students pace themselves to complete the test on time. Providing emotional support. Last but not least, reduce anxiety for the students. Taking a test in a language other than one’s own is a daunting task in and of itself. Help students understand that standardized exams are just one of many ways to measure what they know. Use other forms of informal and authentic measures in the classroom frequently to gain a more holistic understanding of the student’s academic development (Faltis & Coulter, 2008). References Faltis, C. J. & Coulter, C. A. (2008). Teaching English learners and immigrant students in secondary schools. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. Foster, (2009). Paired Passages: Linking fact to fiction. Westminster, CA: Teacher Created Resources. Reiss, J. (2008). 102 content strategies for English language learner. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. About the Author Soyong Lee is an assistant professor in the Bilingual Education/TESOL program at the City College of New York where she teaches both in-service and pre-service ESL teachers and bilingual teachers. Her research interests lie in the linguistic as well as the sociocultural context of language and literacy development among children who are learning English as a new language and children who are bilingual. She is also interested in issues of teacher reflection among teachers of minority students. Her most recent publication, Listening to teacher lore: The challenges and resources of Korean heritage language teachers, in the journal of Teaching and Teacher Education, reflects her interest in heritage language teachers and their opportunities for professional development. |